Ukrainian curator Katya Taylor reflects on language, identity, and art as a decolonization tool

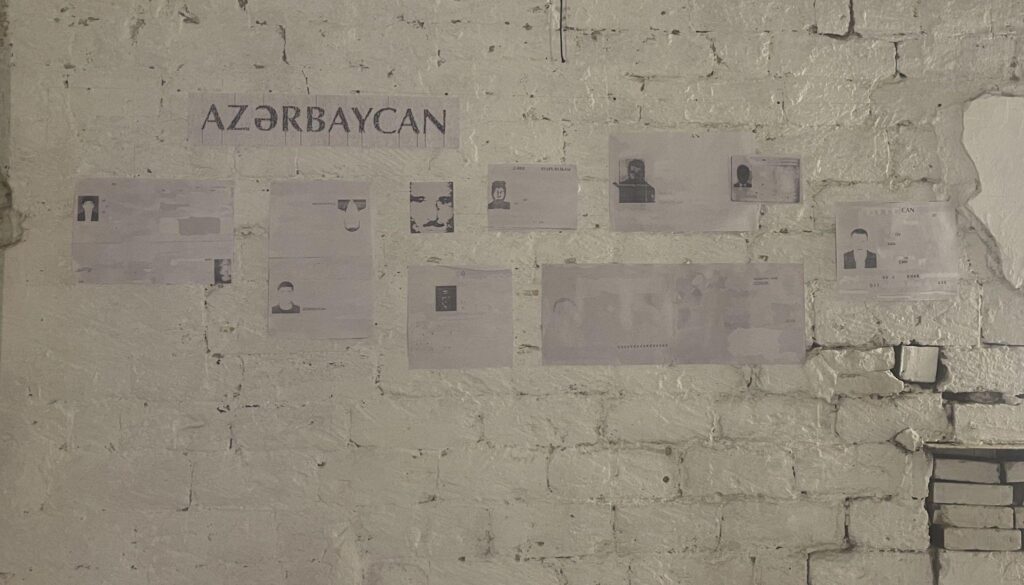

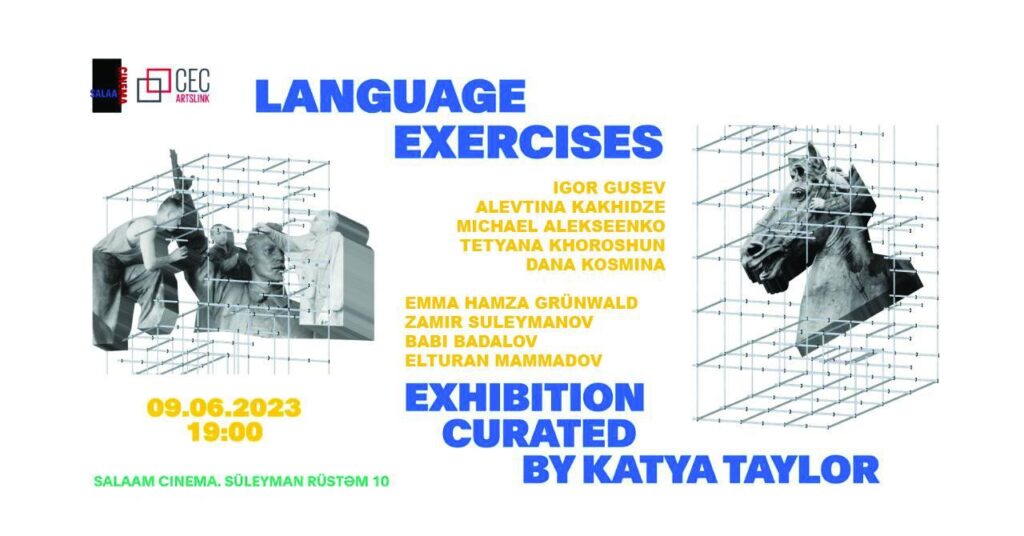

Ukrainian curator and cultural producer Katya Taylor curated the exhibition Language Exercises at Salaam Cinema Baku during her CEC ArtsLink’s Art Prospect Network Residency in Azerbaijan in May – June 2023. The exhibition investigated decolonial processes and experiences of Ukrainians and Azerbaijanis, featuring artworks by contemporary artists from both countries.

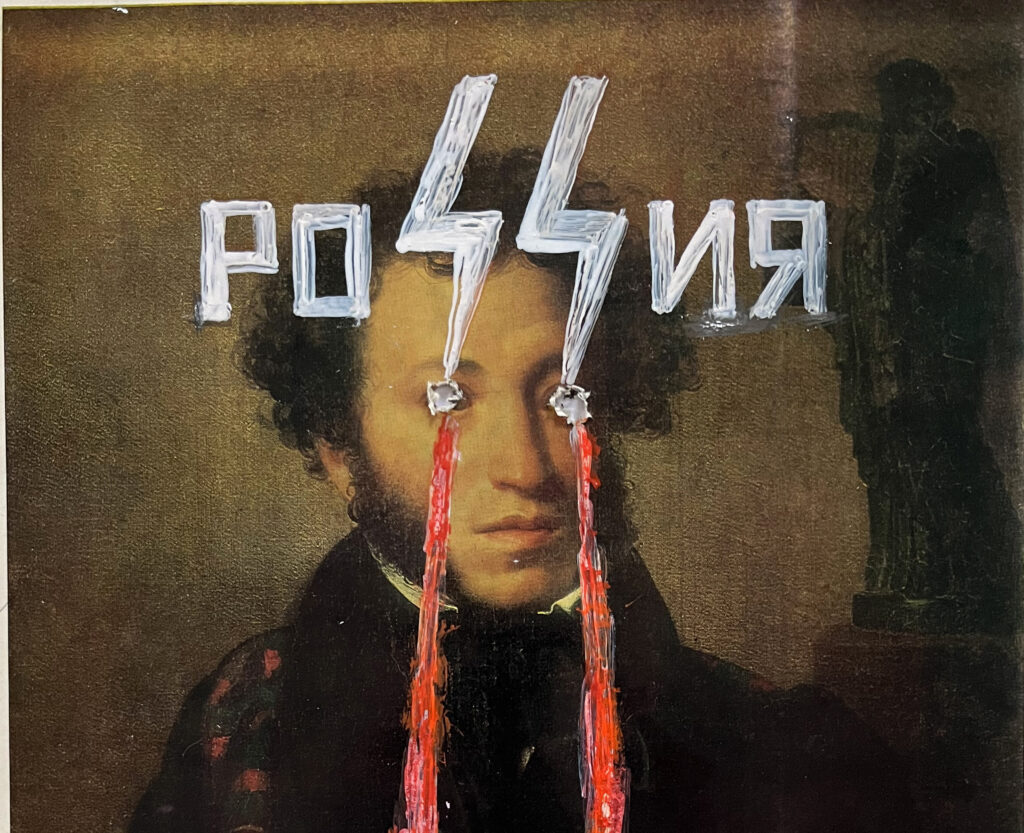

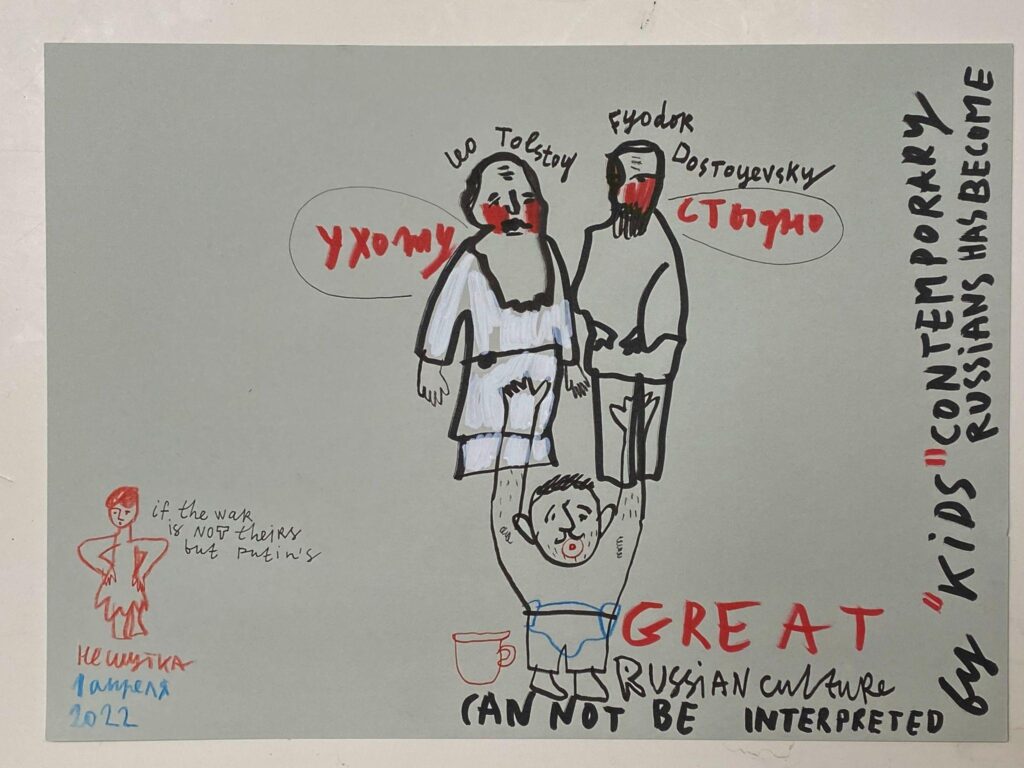

Language Exercises opened a dialogue between artists and audiences, encouraging examination of daily life through the lens of colonial legacies, delving into the subjects of identity, culture, traditions and, particularly, language. While North Azerbaijani – a Turkic language – is spoken by the majority of the country’s people, Russian plays a significant role in education and communication, especially in urban centers. The urgency of Katya’s curatorial perspective was informed by Ukraine’s harrowing reckoning with colonial legacies, including those of Russian language, on the current fields of war.

Katya’s residency notes, originally posted on social media and shared here with her permission, viscerally reflect her experience and the thought process behind its transformation into an impactful curatorial work.